The really sad thing here is that I know very little about my grandparents, Porter William and Eveline (Bonorden) Gifford. He died in 1941, when my father was only 23. I don’t think that my father knew his father very well, either. My grandfather was away in Honduras building railroads for United Fruit for much of my father’s childhood. He used to joke about growing up in a house full of women, his mother and two significantly older sisters and at least one maid. Later in life, my father wrote a biography of his father. A friend of his who read it said that it was a good written record of my grandfather’s business career, but he didn’t feel that the reader would learn anything about my grandfather as a person or as a father. But my father didn’t have anything more to say about his father, so he retitled it as a “Business Biography”. This seems to be a family tradition now: fathers and sons who don’t know each other well.

Although he was the youngest, after his father died, my father was groomed to take over the running of the company his father had founded in Dallas. His older sisters were not allowed to be involved, of course. The most famous project that the company was involved in is the triple underpass under the railroad at the western end of downtown Dallas where, in 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated.

I never met my grandfather and, although Eveline died when I was twenty, she was not very approachable and her life is as much a mystery to me, even though we often had Sunday dinner at her house. She and my father would talk business and my brothers and I would amuse ourselves. Oddly enough, after she died we found a box with a hand-drawn family tree, many old family pictures and Civil War memorabilia. She probably put the tree together from her mother’s bible that she also had. Fortunately no one else in the family was interested in these things except my father and me. This is how we got started in our genealogical research. It was one of the few things that we bonded over. But the bonding was difficult.

Fortunately, a great deal is known about the Bonordens because they were very accomplished and well researched. And, again, the military is helpful. So we go back to the un-united German states of the mid 19th century. There is a book with a very detailed history of the Bonorden family written by a distant relative. But I’ll just give you some highlights. The name is thought to come from the phrase “bie Norden” (in the North) because they came from a small area to the north of the region between the Bucke Mountains and Schaumburg Forest. The name is first seen mentioned on a bill of sale in the records of the town of Stadthagen in 1493. I would have a map here, but the frequently changing borders makes it hard to get an accurate one. Skipping many generations, and interesting stories, I will begin with the first of several physicians. I have names for their wives but know nothing about them or their families, so this account, as with many, is male-centric.

Hermann Friedrich Bonorden (the first of three), born in 1710, is known to have been a surgeon through his death certificate. We know from the births of his children that he lived in Herford, but there is no record of his practicing surgery there. This is the beginning of the line of Herford Bonordens. Other than that, very little is known about his life. So it is assumed that he was a surgeon in the Prussian military. This would require strict training and testing in surgical schools and hospitals. A military surgeon would hold an officer’s rank and be commensurately paid. Surgeons in the Prussian military at that time were responsible for the total care of the soldiers, in both war and peace. They also cared for civilians who could not afford the university trained physicians. However, rosters of military surgical schools and hospitals were seldom kept, so we cannot say exactly where Hermann practiced.

Hermann’s son, Johann Heinrich Bonorden, born in Herford in 1736, was also a military surgeon, but there is much more information about him than his father. He was the Royal Prussian Company Assistant Medical Officer in the Grenadier Company of the 2nd Infantry of the Moselle, No. 11 (whatever all that means). He was also the first official city and county surgeon. In addition, his surgical skills led him to be named the official prison surgeon and district surgeon. All of these positions were highly prized and are evidence of the esteem in which he was held. He lived to the very old age of 75 in 1811.

Johann’s only child, Phillip Heinrich Bonorden, was born in Herford in 1771. As a student at the Friedrichs Gymnasium, he was required, starting at age 11, to give a public speech. The topic of his first speech was “On Fashion”, the next was “The Advantages of Studying”, then “By What Means did the Popes Reach their Heights?” and, finally, at 17, “The Joys of the Heart and of the Mind”. However he failed the “Arbiter” ( a Regents Exam). This exam required that he translate Horace from the Latin, prepare a Latin essay on “About the History of the Science and Pharmacology in Ancient Times”. His German essay was “What Value Does History Have for Us?” (very apropos).

Somehow he managed to enroll in the Halle University a month after the failed exam (there must have been retakes) and also to become a physician. As the official physician of the Bunde District, he supported the use of the controversial smallpox vaccine.

He appears to have had a sense of humor. He was well recognized among his neighbors because of his habit of walking back and forth in front of his house in his pajamas. When asked by a policeman whether he owned a dog, he replied “no” for several days before admitting that he had no dog, but he did have a puppy, which he then pulled from his pajama pocket. Well, it was probably funny at the time.

Philip’s first wife, Dorothea Auguste Nandorf, died of typhus. Their son, Hermann Friedrich Bonorden, also a physician (the 8th in nine generations), would later make a study of the causes of typhus. He was born in 1801 in Herford but later retired in Cologne and so began the Cologne branch of the family.

Hermann Friedrich’s first wife was Marie Charlotte Gossauer, who bore him nine children before dying in 1851. Like his grandfather, he served as a military surgeon but was also a renown medical researcher. Hermann Friedrich published articles on several diseases, including syphilis. His scientific work won him a professorship at the Friedrich Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. He was awarded most of the prestigious honors in medicine at the time. He was also a mycologist. His best known publication is his Complete Mycological Handbook, published in 1851. Of Hermann and Marie’s nine children, one immigrated to America in 1854 or 1859, depending on which census you look at, and settled in Iowa, of course. This was only a few years after the revolution of 1848 in Germany.

Prussia was the largest of the 39 German-speaking states, or kingdoms, of the German Confederation, a loose association meant to balance the power between its two dominant states, Austria and Prussia. However, in 1848, crowds of people gathered demanding freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, arming of the people and a national German parliament. Overwhelmed by this pressure, King Frederick William IV of Prussia yielded verbally to all the demonstrators’ demands.

But the king soon refused to “pick up a crown from the gutter” and unilaterally imposed a monarchist Constitution on Prussia as a way to undercut the democratic forces. As a result, the grip of the landowning classes, the Junkers, remained unbroken. By 1892, Prussia had acquired all of the German states.

Thousands of middle class liberals fled abroad, especially to the United States. This wave of political refugees became known as Forty-Eighters. Many of these German immigrants made their way to the Midwest. They settled into tight-knit German-speaking communities across the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys but quickly adopted their new country.

According to Joseph Eiboeck, a veteran German newspaperman, in his book, Die Deutschen von Iowa und deren Errungenschaften (The Germans of Iowa and Their Achievements), Davenport was “the most German city, not only in the State, but in all the Middle West, the center of all German activities in the State”. But this is not surprising. A large number of Germans settled in Davenport. But German customs sometimes clashed with those of their Irish and Yankee neighbors. While the Germans lived on the western side of the town, non-Germans would usually reside in the eastern part, with Harrison Street being the dividing line.

The main issues of contention were temperance and Sabbath laws. The German and Irish had no problem with each other in their love of beer, lager and ale. But despite the German opposition, a strict state law was passed in 1855 forbidding the sale and production of alcohol in Iowa. The law led to a full-blown riot – called the “Whiskey Riot” – when Germans challenged the authorities’ seizure of liquor. As the size of the heavily voting German community increased, the law was weakened to leave temperance laws to each community.

Still, the “Anglo-Americans” couldn’t swallow the Sunday afternoon picnics and parades.

The population has a preponderating element of the German race, who carry with them, along with their love of lager, sour-krout [sic] and Bolognas, their free and easy habits of Sunday afternoon diversion. At the “Dutch Gardens,” as they call one place of amusement, I saw on Sunday afternoon several hundred people swigging lager on benches under the trees whilst listening to the strains of a fine band.

In 1859 Sunday “Blue Laws” were passed to curb the Germans’ Sunday amusements, closing all gardens, dancing saloons and other places of amusement Germans regularly frequented. However, after two weeks, the ordinance was repealed following massive German protests.

In 1854, the Saratoga docked in New York from Liverpool with refugees of revolution and deposited them at the immigration facility on Ellis Island. Among them were Ludwig Ferdinand Dӧllinger, a shopkeeper, and his wife Sofie Fredericke and their children, Herman, age 15, Gustave, age 11, Emma, age 7 and Clara, an infant. Although they considered themselves to be German, they had begun their journey in Prussia.

On another ship, at about the same time, Herman Frederich Bonorden left his home in Prussia and came to America alone in his twenties in 1859. His parents and maybe even his two brothers remained behind in Prussia. Perhaps Herman Frederich left Prussia to make a name for himself, separate from his famous father. (At least he spelled it differently.)

Herman F. Bonorden

Two years after arriving in America, on August 16, 1861, Herman was in Davenport, Iowa, and drafted for three years as a bugler in Company E, 2nd Iowa Cavalry, which became part of the Army of the Mississippi. He may have seen action at Monterey, Tennessee and Farmingham, Mississippi in April and May of 1862. But war did not seem to suit Herman. On May 10, 1862, Herman was put on “extra duty clerk in Q.M. Dpt.” in the pay department. He remained there for the duration of the war. That’s all I know about his service.

Emma Auguste Dӧllinger

But I have learned quite a bit about the service of Emma’s brother Herman Dӧllinger (not to be confused with her future husband Herman Bonorden) who also served in the American Civil War from its beginning to its end, and kept a diary as well. The diary has been transcribed by Floyd Kallum, a Bonorden descendent, and copied and bound. It has a wonderful introduction concerning who Herman was and how the diary came to be in Floyd’s hand, but as Floyd quotes Napoleon, “Above all, be distrustful of eyewitnesses, – the only things my Grenadiers saw of Russia was the pack of the man in from.” Maybe that’s what Napoleon wanted historians to believe.

But there seems to be some truth to that. I have always been disappointed that Porter Wallace Roundy was not a more vigorous writer in his diary that he sort of kept at City Point, Virginia. As a hospital steward, he must have seen so much more than the back of the soldier in front of him. But, most likely, what he saw was too horrid to describe or even want to remember.

All of this is by way of apology for not giving you any tidbits from Herman Döllinger’s diary. I have picked it up several times to read. As he writes, “nothing of importance” happened most days. When things became eventful, there was no time to write and probably no wish to record. As many have said, war is mostly long periods of excruciating boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.

Floyd adds a lot of commentary along the way to give some context to Herman’s observations. On page 15 he notes that Herman Döllinger served with his future brother-in-law, Herman Frederich Bonorden at Corinth, Mississippi on May 9, 1862, when the 2nd Iowa Cavalry joined with the 56th Illinois Volunteers and other regiments for the attack on Corinth. It was actually not much of a battle. After the enormous losses at the Union victory at Shiloh just days before, General Grant took it slow in advancing on the Confederate retreat. But the Confederates staged a ruse, leaving a few troops at Corinth lighting fires, drumming, and making all sorts of racket while the Confederate army slipped quietly to safety.

In 1859 Sunday “Blue Laws” were passed to curb the Germans’ Sunday amusements, closing all gardens, dancing saloons and other places of amusement Germans regularly frequented. However, after two weeks, the ordinance was repealed following massive German protests.

In 1854, the Saratoga docked in New York from Liverpool with refugees of revolution and deposited them at the immigration facility on Ellis Island. Among them were Ludwig Ferdinand Dӧllinger, a shopkeeper, and his wife Sofie Fredericke and their children, Herman, age 15, Gustave, age 11, Emma, age 7 and Clara, an infant. Although they considered themselves to be German, they had begun their journey in Prussia.

On another ship, at about the same time, Herman Frederich Bonorden left his home in Prussia and came to America alone in his twenties in 1859. His parents and maybe even his two brothers remained behind in Prussia. Perhaps Herman Frederich left Prussia to make a name for himself, separate from his famous father. (At least he spelled it differently.)

Two years after arriving in America, on August 16, 1861, Herman was in Davenport, Iowa, and drafted for three years as a bugler in Company E, 2nd Iowa Cavalry, which became part of the Army of the Mississippi. He may have seen action at Monterey, Tennessee and Farmingham, Mississippi in April and May of 1862. But war did not seem to suit Herman. On May 10, 1862, Herman was put on “extra duty clerk in Q.M. Dpt.” in the pay department. He remained there for the duration of the war. That’s all I know about his service.

But I have learned quite a bit about the service of Emma’s brother Herman Dӧllinger (not to be confused with her future husband Herman Bonorden) who also served in the American Civil War from its beginning to its end, and kept a diary as well. The diary has been transcribed by Floyd Kallum, a Bonorden descendent, and copied and bound. It has a wonderful introduction concerning who Herman was and how the diary came to be in Floyd’s hand, but as Floyd quotes Napoleon, “Above all, be distrustful of eyewitnesses, – the only things my Grenadiers saw of Russia was the pack of the man in from.” Maybe that’s what Napoleon wanted historians to believe.

But there seems to be some truth to that. I have always been disappointed that Porter Wallace Roundy was not a more vigorous writer in his diary that he sort of kept at City Point, Virginia. As a hospital steward, he must have seen so much more than the back of the soldier in front of him. But, most likely, what he saw was too horrid to describe or even want to remember.

All of this is by way of apology for not giving you any tidbits from Herman Döllinger’s diary. I have picked it up several times to read. As he writes, “nothing of importance” happened most days. When things became eventful, there was no time to write and probably no wish to record. As many have said, war is mostly long periods of excruciating boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.

Floyd adds a lot of commentary along the way to give some context to Herman’s observations. On page 15 he notes that Herman Döllinger served with his future brother-in-law, Herman Frederich Bonorden at Corinth, Mississippi on May 9, 1862, when the 2nd Iowa Cavalry joined with the 56th Illinois Volunteers and other regiments for the attack on Corinth. It was actually not much of a battle. After the enormous losses at the Union victory at Shiloh just days before, General Grant took it slow in advancing on the Confederate retreat. But the Confederates staged a ruse, leaving a few troops at Corinth lighting fires, drumming, and making all sorts of racket while the Confederate army slipped quietly to safety.

There is one entry, on January 1, 1863, that is worth quoting, along with Herman’s creative spelling.

Continued our march this morning early toward Lafyette [Tennessee], after marching about 1 mile, and was about to passe a house a lady came out, and complaint about the soldears taking her chickens, and all her turnips, and wanted the Col. to guard them, the Col. askt her, wheather she wanted the Government torn down, she said, she did not, then he askt her wheather she wanted the Confedracy to be establishet, she said she did, and that she was a southern women, the Col. apliet, if that is the case, i donat Care, if the[y] eat up your house and home, at that time we all jumpt in to her tirnip pach, and get all we wanted.

There are no entries after December 31, 1963, when he came to the last page of the diary for that year. However, Herman continued to serve, eventually under General Sherman on his March to the Sea. After the surrender of the Confederacy, the Union Army began sending its troops home to be mustered out.

Sargent Herman F. Dellinger (or Dillinger, the army was never sure how to spell it but always got it wrong probably because of the umlaud, ö) was on the first leg of his long journey to Springfield, Illinois on board the U. S. Steam Transport “General Lyon”, along with about 500 to 600 others, including women, children and freedmen. The ship was bound from Wilmington, North Carolina to Fortress Monroe in Virginia, at the opening of Chesapeake Bay. On March 31, 1865, when off Cape Hatteras, a storm was encountered and the “General Lyon” caught fire and sank. Only twenty-eight persons were saved.

Herman may have sent his diaries to his and Emma’s mother, Sophie Fredericka, as he completed them, but the last one was probably with him on the General Lyon. It has never been found. The Adjutant General’s Report lists all member of the 56th Illinois Volunteer Infantry and their fates.

After the war Herman Frederich Bonorden applied for US citizenship, which he received in Sept, 1864 in St. Louis. Then, in September 1865, he married Herman Döllinger’s sister, Emma Auguste Dӧllinger, in St. Louis. We don’t know where Emma was living before she met Herman, but maybe it was St. Louis. It’s impossible to know if the Dӧllingers and Bonordens knew each other in Prussia. I have no information about the Dӧllinger family prior to their immigration to America. It appears that Emma’s father, Ludwig Ferdinand, returned to Germany, where he died four years after leaving. He may have been ill when disembarking at Ellis Island and not allowed to stay.

After their marriage, Emma and Herman returned to Iowa from St. Louis and Herman was admitted to the Iowa State Bar. He practiced as an attorney at law in Iowa City, where they raised their nine children. Iowa City is only about 50 miles west of Davenport. I have an old German bible in which Emma kept the records, in German, of the births in the family. There is no evidence that Herman returned to Davenport after the war. If he had lived there, he may have met Porter Wallace Roundy, also a Civil War veteran, and his daughter, Nettie May, and his grandsons, Edward and William Gifford. But it is safe to assume that Herman’s daughter Eveline met Edward H. Gifford’s son Porter because of mutual friends in Davenport.

Then, amazingly, with seven children to feed, clothe and educate, and a mother-in-law to care for, Herman decided to change professions. In 1887, he went to Washington and applied to the Bureau of Pensions to be a pension examiner. That same year he applied for a disability pension for himself based on his service in the War of the Rebellion. His family remained in their home in Iowa City, Iowa and then Quincy, Illinois while Herman traveled for work in Illinois, Missouri and Washington as a pension examiner. When Emma died in 1900 at the age of 55, she left Herman to raise their four youngest children who were all teenagers by then.

So, even as he claimed to be disabled to the extent of being “totally unable to earn a support by manual labor”, he worked as a pension examiner for seventeen years. In 1907, he applied for an increase in his pension shortly after Congress approved such increases. In fact, it seems that every time Congress passed a new pension act, Herman had his application ready.

Eventually, he no longer needed to plead a disability, only his war record. In 1910, at 75, he was living in Washington, DC, with his daughter Bertha (unfortunate name; she looked like a Bertha) and stated that he had been working as a pension examiner for 16 years. In 1911, he and his daughter Bertha moved to San Diego, California, and Herman applied for a transfer of his pension to his new address. In this case, the six month residency requirement for the transfer was waived by H. R. C. Shaw, Chief, Certificate Division, based on reliable information from Herman’s colleague, Mr. Works, that “pensioner intends to make San Diego his permanent home.” It’s good to have friends in the Pension Office.

Finally, in 1912, he wrote to J. L Davenport, Commissioner of Pensions in Washington (errors in the original).

Dear Sir; I hope that you upon seeing the signature below, will remember the Special-Examiner and Clerk that worked in the Bureau from Aug. 1887 to Sept, 15” 191[?]., and had to resign on account of the failure of his eye-sight, to make room for some one else, more phisically able to perform his duties. Since September last I have lived here [San Diego] with one of my daughters, as a poor relation on my $20.00 per month pension. I am poor in health and financially; saved only a small amount of money during my civil service. My wife died years ago, leaving me with a large and expensive family which used up most of my salary….June 30 last I was 77 years of age and will not live very long, I am almost blind on account of which I use a type-writer. I respectfully ask you to do a favor to a former faithful and efficient employee of the Bureau and if not contrary to your duties, to make my case “Special” so I can draw the increase at San Francisco, Cal. September 4” next and I will thank you ever so much. A premium on a life policy is due early in Oct.

It appears that his case may not have been treated as “Special”. Three years after this letter, Herman was sent another form to fill out for his pension. But he apparently did eventually receive an increase in his pension. In 1917, his pension check for $90 (which is way more than $20) was returned to the Pension Office “because the pensioner died Apr 30 1917”. The check had been mailed, ironically, to the “Fredericka Home for the Aged”.

This is, indeed, a sad, but perplexing tale. It’s surprising that a man who was a lawyer for 18 years and then a Pension Examiner for another 17 years could not have saved for his retirement. And when his wife Emma died in 1900, the “large and expensive family” she left him with was composed of the four youngest children. The eldest of these, Otto, age 22, would soon marry and was probably helping to support the family; the next eldest, Bertha, age 20, would care for Herman until his death. She never married and lived alone after her father’s death until her own in 1945. The other two, Eveline, 16, and Richard, 13, would not be home much longer.

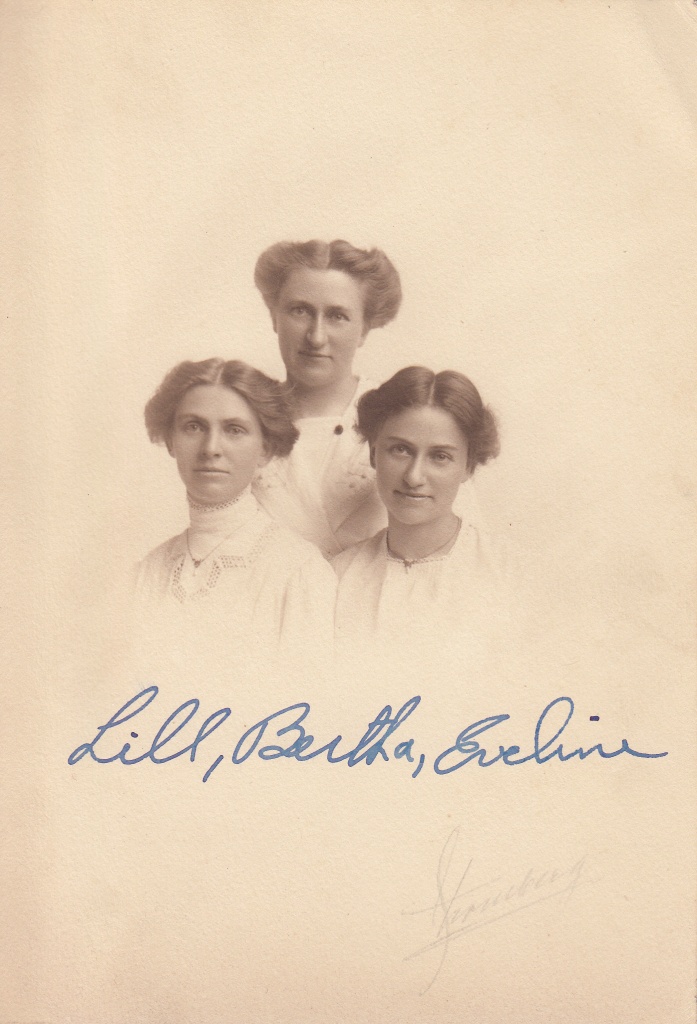

Here is a photograph of the eight siblings on the only occasion they were all together. My grandmother, Eveline is second from the right.

In 1907, Herman and Emma’s daughter Eveline married Porter William Gifford (Sr), the son of Edmond (Edward) H. Gifford and Nettie May Roundy, and grandson of Edmond J. Gifford and Nancy Ann Renfro. Porter was 22 years old and Eveline was 25 years old. Eveline and Porter had three children: Edna May, Marjorie, and Porter William, Jr, my father, born in 1918 in Dallas. I believe that this long line of distant fathers and their sons left its mark on my father.

Porter worked for the Walsh Construction Company of Davenport. In 1906 he formed a subcontracting partnership, Walsh, List and Gifford construction company, with Bill List. They probably moved frequently to live near the job sights. By 1918, they had moved to Biloxi, Mississippi where the children’s grandfathers, Porter Wallace Roundy and Edward H. Gifford, visited them.

Then, throughout the twenties, Porter, sometimes with Eveline, traveled to Honduras with the Vaccaro family. I count 13 trips in those ten years, some of them with Eveline returning home alone. Porter’s Company built railroads from the Vaccaro’s banana plantations to the port of La Ceiba for shipping the bananas to the U. S. He looks like a giant in this picture and he was quite tall. But I think these “Caribs” are children.

Porter and Eveline eventually settled in Dallas, Texas. They would move next door to Dr. Felix L. Butte, another descendant of German immigrants, and his wife, Elizabeth (Kirkpatrick) and their three children. Their son, affectionately known as “Pete”, would marry the girl next door.

Oh MY GOD!! We are cousins and you have photographs I have never seen before. Hermann G. Bonorden was my great grandfather.

Eleanor Bonorden Brundick

LikeLike

Hello, Eleanor, what a surprise! Send me an email and tell me about yourself.

LikeLike

Sgifford213@gmail.com

LikeLike